Way back in the summer of 2010, the InRO staff planned a series of articles that each paired two recent (i.e. post-2000) Westerns. The project fell through, but not before I’d written my assignment: a retrospective on Seraphim Falls and The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada. My editor at InRO recently posted that article to celebrate the release of Meek’s Cutoff.

The spectre of death is as present in the Western genre as leather, horses and guns, and it nearly always comes in the form of homicide. Characters don’t die by accident or illness — if you own a ranch or a saloon in the classic American West, or if you wear a badge or ride where the wind takes you, expect to meet your maker with the help of a bullet. Death at the hands of another is inscribed onto every plot and every finale, a solution to treachery and wrongdoing of all stripes, an art practiced by the good and the bad. The genre’s images of death are loud, dusty and sudden, but they aren’t always as cut and dried as a gunshot at high noon. In some Westerns, death isn’t a full stop but a beginning, of sorts. The leather and the dust lose materiality and give way to the supernatural, while the landscape onscreen reveals itself to be a halfway space between the hard world and the afterlife, where matter itself is doubtful, and where characters set for a time to sort through their differences, which almost always amount to questions of honor and revenge.

Death can be more than a drop to the ground or a tombstone on the outskirts of town. It can be even more animated than the sight of Django dragging his own coffin through the dirt. In some Westerns, death comes back to deal with unfinished business or to lend a helping hand–it looks like Clint Eastwood but it’s really an avenging angel bent on killing his own killers or protecting the innocent. The righteous supernatural limes classic Westerns like “High Plains Drifter” and “Pale Rider” with a not-quite-workaday gleam that tightens our skins, as if a ghost had brushed us by. The horses, dust and leather exist in the service of something more than order or Manifest Destiny–the seeker’s quest for revenge is so urgent that it transcends the laws of nature. Two recent Westerns have hitched their wagons to the arcane tradition of “High Plains Drifter” and veered into the occult; the occult is in fact what lifts David Von Ancken’s “Seraphim Falls” (2007) and Tommy Lee Jones’ “The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada” (2005) above the sum of their mediocre parts. Though neither amounts to the same cinematic quotient of better films like “The Proposition” and “There Will Be Blood,” they’re notable for being revisionist Westerns of a very interesting kind, one that uses the avenging-angel trope with ease–even aplomb. (They’re certainly no worse than their Eastwood predecessors which, in the clear light of the Aughts, fall short of the work of Leone, Ford or Siegel, never mind Hillcoat or Anderson.)

If you know your Westerns and your Christian lore, you’ll anticipate the uncanny substance of “Seraphim Falls” the moment you read the title. The undead are bound to appear, and the viewer’s only task is figuring out which of the two leads is the fallen man-angel driven back to earth by honor and burning for vengeance. The scene opens on Nevada’s Ruby Mountain, where a man (Pierce Brosnan) is being pursued by a posse led by Carver (Liam Neeson). It’s some time before we learn why Carver wants revenge, but his prey is evidently a survivor who can overcome bullet wounds and icy torrents. Over the course of the movie, the landscape shifts from wintry mountains to thermal sand flats; as the topography morphs, so do our protagonist/antagonist convictions. Carver, who was cinematically earmarked as a villain at movie’s start–all dark colors and looming threat–is revealed to be the husband wronged, while our supposed hero, Gideon, lives up to his biblical name as a destroyer (he burned down Carver’s home and killed his family while rooting out rebels on Gen. Sherman’s orders). Good and Bad are collapsed poles, something rare in avenging-angel Westerns: Gideon is an accidental villain, at worst, who’s thirsty for understanding if not redemption, and Carver is motivated by honor rather than bloodlust, a passably positive vigilante.

“Seraphim Falls” lacks a light touch both symbolically and emotionally. It gives into sentiment in spots and indulges in clichéd short-hand that a stronger script would have avoided (e.g. the tired dynamic between visitor and boy in the ranch house where Gideon recovers from his wounds). This isn’t a revisionist Western that aims to defy or even subvert old, mottled signatures, and it manages to tip into the laughable at times. It also worships Jarmusch’s “Dead Man” shamelessly in its third act–down to the top-hatted Native American Elder and a canted, surreal tone. But that tone, to be fair, is appropriate to a narrative about one or possibly two dead men resolving their conflict in limbo. We aren’t precisely sure, after all, that Carver is an occult force; we only know that we last saw him being arrested for the capital crime of treason, and that he fades from the landscape in the final shot (along with Gideon, who may have died in that icy river), the same way Eastwood did at the end of “High Plains Drifter.” We know he falls asleep to violent flashbacks like Eastwood’s drifter did–visions of the events that triggered a need for revenge forceful enough to put off the grave. We know he inhabits a land of lost souls: bandits, mercenaries, chain gangs, religious zealots, even a pickpocket with a cherubic face. And we know–at least we’re pretty sure–that the devil herself comes calling in the form of a nostrum seller in a red dress. Anjelica Huston’s Madame Louise draws her caravan alongside each man as they struggle through the desert on their way to the final showdown. She takes what’s left of their ‘lives’–water, horse–and presses guns and bullets into their hands. She sees the contest through, in other words, in a surreal scene that compensates for the movie’s earlier flaws and wraps up its supernatural work with a satisfying death rattle.

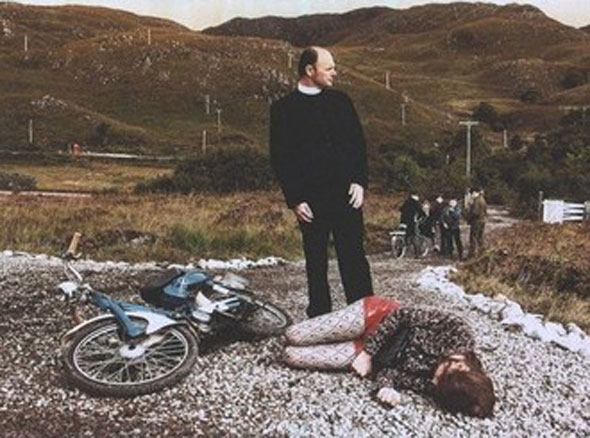

If “Seraphim Falls” is a mediocre entry into the Western genre as a whole, it’s a welcome addition to the avenging-angel subgenre, at least as far as its treatment of that trope, which is lovingly attended to. “The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada” is successful in a similar way. Taken as a whole, it’s a derivate vanity project with a contrived Guillermo Arriaga script (the same writer who gave us the self-important “Amores Perros,” “21 Grams” and “Babel”). But taken as an avenging-angel study, it works well enough (and, to be fair, the Arriaga gaga is toned down in Jones’ hands). The wronged man in question rides on the shoulders of his avenger, this time, but ‘Three Burials’ is very much about the dead who won’t stay dead until their honor is satisfied. Melquiades Estrada (Julio César Cedillo), who’s died at least twice, refuses to stay buried and tags along, “Weekend at Bernie’s”-style, on a horseback trek from Texas to Mexico. In (second?) life, he was a cowboy who worked on Pete Perkins’ (Jones) ranch and forged a close friendship with his employer. When he’s accidentally shot by a nervous border-patrol rookie (Barry Pepper), his corpse is dumped in the desert (the first burial), processed by the state (the second burial), then exhumed by Perkins and his killer and hauled, without dignity, to his beloved Jiminez–his final resting place. The burial triptych is a bit smug and Arriaga’s study of US/Mexican border tensions a bit pandering, but the former has metaphorical purpose within the supernatural Western subgenre, and the latter provides the action with a starting point.

Pepper’s Mike Norton is a brutal man–an inconsiderate lover and a bully-authority who breaks immigrants’ noses. Arriaga’s script is unforgiving when it comes to portraying the bone-crunching bigotry of Texas authority, and it merges in interesting ways with Jones’ romanticized good old boys who are bathed in fond light and dulcet cadences. Perkins, who can see the humanity in illegal immigrants effortlessly, is a foil to Norton, who needs to take an extended journey in order to discover the same. When the local sheriff (Dwight Yoakam) refuses to pursue Estrada’s murder, Perkins takes the law into his own hands as blithely as the Man With No Name; he’d promised his friend some time back that he’d see to it Mel was buried in Jiminez should he happen die in Texas. Since Mel isn’t around to avenge his own death–at least directly–Perkins steps in: he pressgangs Norton into helping him bear his friend’s corpse down south, using his fists and a whole lot of rope to shock the younger man into submission.

‘Three Burials’ is a watchable film, if only for the performances (Jones is his typically subdued self, while Pepper’s chewier style is just angular enough convince). The friendship between Perkins and Mel (seen mostly in flashback) is tender and the world around them–a precinct of trailer-homes, diners, and soap operas–mostly eschews the off-kilter feel of Ancken’s last act. Jones, pinging us with all the standard Western cues, tries to make his landscape speak; he’s no Malick or even a Coen Brother, but he services the story and mood well enough. He attempts (with the help of Arriaga) to plug a few tufts of the absurd into the proceedings, which will work for some viewers and fail for others (though that harrowing shot of a packhorse tipping off the side of a canyon path is a universal crowd-pleaser, I’m sure–like Gideon leaping out of the stomach of a dead horse in “Seraphim Falls.” Overwrought? Absolutely. But still among the most interesting moments of each film). Jones knows what trope he’s dealing with, and if the viewer misses the supernatural prompts he posts along the way, we cross them head-on in the last act, when an old photo and the Jiminez locals suggest Mel died years ago.

Arriaga and Jones have jettisoned the avenging-angel trope into a broader sphere– where Eastwood and Neeson agitate to restore the honor of a single man or, at most, a single clan of gold-miners, the character of Mel (liminal as he is) deploys Jones’s Perkins to restore the honor of an entire people. When Mel is buried in Jiminez by a remorseful, re-educated Norton, satisfaction is returned for every “pollo” and every American of Latinx descent who was ever wronged by a slur. Norton’s epiphany is meant to be understood in macrocosm, as is Jones’s privileged compassion. It’s a very contemporary, very germane revision of the avenging-angel subgenre–it held my interest as a text, at least, in the same way that “Seraphim Falls” did. Despite both films’ tendency to mainstream sentiment and technique, Ancken and Jones update their chosen Western subgenre with reverence and even wisdom. ‘Three Burials’ and “Seraphim Falls” form an indispensible double-bill, in fact, for those asking themselves what’s become of the Pale Rider.